|

That Dangerous Perspective

Frances Noble talks to Ivy Smith, the painter

Where did you study?

I went to the local art school in Walthamstow and did the equivalent of a foundation year. Then I went to Central St. Martins for a little less than a year to study graphics, before finding that wasn’t my subject and transferring to Chelsea Art School and finishing my degree doing painting, with print-making as a subsidiary subject. I did a three-year post-graduate course at the Royal Academy Schools, which confirmed me in my commitment to painting and enabled me to work in a wonderful environment.

Who were the artists and what were the styles which influenced you most?

While I was at Chelsea it was the clear outlines and pure colour of Rogier van der Weyden which most inspired me. I

admired the positioning of the figures and the way the artist seemed to look down onto them, tilting and distorting the perspective to get the shapes and compositional effect he sought. Norman Blamey was an inspirational teacher and I am still a great admirer of his work. I liked people like Stanley Spencer, both John and Paul Nash and Edward Bawden - the work which came from between the wars. But I am never sure about the importance of these early influences because I think what happens is much more that you have some internal feeling about the way you want to work, and when you find that technique or style has been successful for someone else, who is already respected, that gives you permission to work like that yourself. I don’t really think that you can ever successfully base your own work on someone else’s. But you can gain confidence in your own work from things which have already been tried. I remember thinking at the Royal Academy Post-Impressionist Exhibition that, although there was a lot of work which seemed Gauguin-like, none of it was as successful as Gauguin’s own pictures and prints. Similarly, although other artists had obviously seen and admired the pointillist works of Seurat, only the original Seurats were truly marvellous.

How did you come to leave London with its vibrant artistic community?

It was a sideways move really. I am a Londoner and when I left the Academy Schools I remember standing in the studio and saying to myself, ’I will never leave London.’ A year later I was in the country! Once I had decided to move out I started looking very widely for the right place to live - Devon, the Midlands, Norfolk. I ended up living in a farm worker’s cottage in Necton (near Swaffham) in the heart of the Norfolk countryside and then at Aylmerton near Cromer for 20 odd years. The country provided a magical, unknown world with house-martins nesting outside my window. But in the end the beauty couldn’t outweigh the isolation and I was beginning to feel out of touch, working alone at home all the time. Norwich became a solution to the isolation - I could live in a city and yet walk out into the countryside every day.

You seem to have two quite

distinct subject ranges - people

and landscapes?

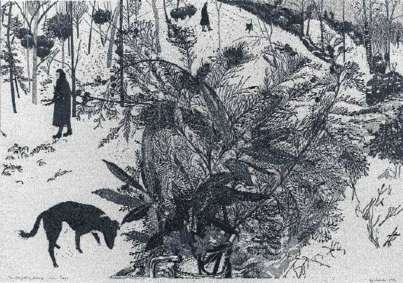

People are my main subject, and mostly, but not entirely, my figure painting is done from drawings and I combine the drawings to achieve the composition which my idea demands. But I like the immediacy of landscapes which can be done on the spot; and I particularly like the way landscape lends itself to a series of works - the beauty of changing seasons at Whitlingham, for example, or the series I made of the garden at Plas Newydd near Llangollen (see opposite). Painting landscapes provides an interlude, a change of pace in my work.

You make prints as well as

paintings, what are the pleasures

and differences of the two

different mediums?

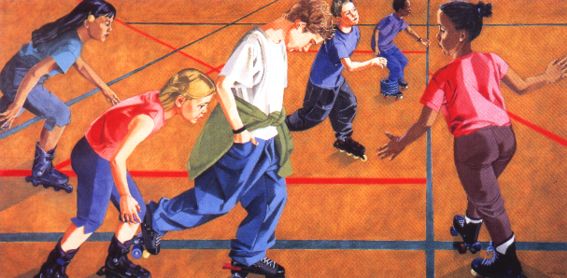

When I’m painting, every mark I make is a decision - painting from life can be a tyrant. In a print I make some big decisions early on and then there are quite lengthy processes to be gone through, including the printing itself, so there is a lot of practical, physical work, interspersed with the thinking. In a painting my hand makes every mark, but in a print the actual qualities of the medium can do some of the work for me. For example, in one of the paintings for the recent commission from the Jerwood Foundation, I painted water which I wanted to appear solid but transparent, so that the bodies of the swimming children could be seen but would be obviously ‘beneath’ the water. In the prints of the swimmers, which I am working on now, I am trying to create the same effect, but without my hand intervening in the process. I am enjoying experimenting with different ways of achieving that. I like the contrast between the two forms of work and the challenge of achieving the finished picture in a way that satisfies me.

Are the pressures of working to commission inhibiting compared to ‘free’ work?

The impetus is different - with a commission there is someone outside, waiting, the audience is already there. Having to meet the brief directs the work somewhere where it might not otherwise have gone. I see commissions as positive things rather than intimidating. They give me courage, in the true sense of the word, encouraging me to meet my responsibility to the sitters and to the commissioner. I can be much braver working on a commission. Because it is quite scary asking someone to pose for me, to have the authority of a commission behind me helps me dare to ask for a sitting! In a commission there is a responsibility to resolve the problems which the picture throws up. Working freely, that resolution may be much harder to achieve. In a way that carries on my answer to your earlier question about painting and print-making; there is a difference in satisfaction between print-making - which must satisfy me as the print-maker - and a commissioned painting which has to satisfy the demands of the commissioner as well as my own.

When I look at your paintings I am always struck that your firmness of line and clarity of form still seems to delineate a great tenderness and respect for your subjects. Is that what you want to display in a finished piece?

I am very pleased you have said that. I really hope that the feeling that goes into my work comes out to meet the audience. My form and line may seem hard because I see form as an abstract thing of shape and colour. This isn’t a theoretical thing, I just constitutionally see shape. So I compose and think in mass, shape and colour. But while I think about my subjects, and think about them doing these things and being these things that I am representing, I become aware of them and feel a tenderness and fondness for that action, that person, even when it’s someone I hardly know. I am always pleased when that feeling comes through in the work.

I was looking at some of Vanessa Bell’s pictures of her children and I don’t get that feeling of tenderness in her work - why do you think that is?

Well she was very involved with theoretical ideas about painting and perhaps those abstract ideas can overcome the humanity of the work.

Do you mind when your audience makes ‘readings’ of your work?

No, not really. I’m not sending messages, but painting things I have really seen, so people can read whatever they want into what I show in my pictures. I do get bothered, though, when people want narratives to explain the composition. I think it’s a very English thing because we are such a literary nation. Why can’t the English just look at a painting and let it be? My pictures don’t have a story - there is no before or after - just the captured moment. For example, in ’The Smith Family Golden Wedding’ which I painted in 1986 the group of people sitting round the table look rather glum and I am always being asked why no-one is smiling, was it a miserable meal? Well, that potential reading didn’t enter into my head when I made the picture. I knew on the day of the party that I wanted to paint the occasion of my parents’ golden wedding anniversary, but it was two years before I was ready to begin. I had to make drawings of all the people who were present, and then place them and the table setting to achieve the composition I needed. It was a return to working from drawings after 15 years. People can’t hold a smile throughout a sitting, they naturally look solemn when they are having their likeness made, and so my working drawings are of solemn faces. Painting smiles onto unsmiling faces would never work - so

you see serious people. But I have learnt from the reactions, and now I lighten

facial expressions by just lifting the expressions slightly.

You won a major prize with that picture, tell me about that.

Yes I did; I had entered work for the John Player / National Portrait Gallery Award seven times and my submission had been accepted by the judges every year. Nineteen eighty six would be my last chance to win, though, because of the age limit, and I decided to pull out all the stops for this one and really go for it. I started the drawings in January and had enough of the picture finished to submit a slide for selection (the short list was prepared from slide submissions). I was shortlisted, but this is a very big picture and it was a mad scramble to get it finished by the closing date. I was still painting it on the morning of the day it had to be delivered! We hired a van to get it from Norwich to London, and we had to be in Trafalgar Square by five. So there we were with this still wet painting in the back of the van heading for London on the A11. We got stuck in the inevitable traffic jam at Red Lodge and arrived at at the National Portrait Gallery at five exactly. We parked the van at the edge of the road and ran in with the picture. Terrifying. But the award ceremony is even worse. In the finest tradition of these things, they announce the results in reverse order and you are left hanging on, expecting to be called every time and hardly daring to hope that this time you will be the winner. There is no gentle pre-warning for anyone. I was so pleased to have won.

I have seen your name on the roll of members of the Art Workers Guild.

What a weird and wonderful institution the Art Workers Guild is. It wasn’t founded by William Morris but he was one of the early Masters and the ethic of the Guild follows a lot of his thinking. You are elected to it by your peers and I was elected in 1991, the same year as Peter Blake. What is especially nice is that it’s all about arts and crafts; no-one is saying painting is intrinsically better than designing a building or a chair, being a letter cutter or working in textiles. It’s all about making things skilfully.

Looking at your pictures it seems impossible to decide what the ‘point of view’ is, but somehow they show credible relationships between the figures or items you represent. Do you ‘see’ your composition from some indefinable point?

I know the viewer of my paintings will have difficulty identifying his or her viewpoint and in deciding where I was when I made the picture. People and things get twisted and turned simply because I want them to be that shape on the canvas, and to make those links with other elements of the composition. So the viewpoint is not consistent and different parts may need to be seen from different positions in front of the picture in order to make sense. My backgrounds may be tipped all over the place and things shoved around so that the relationships of the people and objects meet my compositional needs. I work on a grid so that a diagonal may be picked up somewhere else in the picture - that can be a purely formal decision of mine. I make the space ’work’ by scale, colour and overlapping. The audience is invited to work, to read from the information contained in the picture, in order to understand what is going on. I actually think perspective is a really dangerous thing, it’s too illusionistic and has to be confounded in some way.

I know you recently spent a day at

a workshop about Byzantine mosaics. As an artist is it threatening to expose yourself to new visual experience?

I went to Rome two years ago expecting to spend time in the Vatican Museum looking at Renaissance paintings, but by the sheerest chance I went into a church and saw some Byzantine mosaics and was totally knocked out by them. So the whole of the rest of the trip was taken up hunting for more mosaics. When I came home I scoured all the guide books I could find looking for places where I could see more, but they only mentioned a few. I asked Atticus Bookshop in Cork Street but even they couldn’t help me much. Eventually I went back to Rome and discovered more mosaics there which were absolutely wonderful, particularly the saints with their simple tunics, their individuality differentiated only by their brooches and sandals. I must have seen the mosaics in St. Marks in Venice when I was young - but I don’t remember them having this effect on me. They were done over a very long period, and for me they lack the drama and conviction of the early Byzantine. I think what has pleased me is how like early tapestry they are. The forms and range of information the medium can convey is limited and yet the overall effect is of richness. The medium forces the artist to be simple - all the gradations of form and colour have to be made in small steps. I suppose I am repeating what I said earlier - what excites an artist is not something new, but the recognition of work which has addressed and found solutions to problems which you experience and try to resolve in your own work.

Do you have a definite routine to work to, or do you wait for inspiration before you start to work?

When I’m working properly and steadily I do my best work in the morning, so any jobs or duties are put back to the afternoon when I’m less effective. On a good day I might work from 8.30 till 4.00 and my friends and family know not to bother me until later in the day. Even Ruby my dog has to wait for her afternoon walk until I have finished!

You have a wonderful Albion Press, wherever did you find it?

I did print-making at college as a

subsidiary subject and for a long time I went back to use their press. But when I came to Norfolk I had no access to a press, until I found there was one at Wingfield College I could use. They were pleased to see it working and I was happy enough with that arrangement. Although I had always wanted a press of my own, I wasn’t actually looking for one, then, one day after a Christmas shopping trip to Norwich, Mark, my partner, had bought a copy of Yachting Monthly to read on the train on the way back to Cromer; that left me with Exchange and Mart to pass the time, and I turned, quite idly, to ‘printing’ and there I found ‘Albion Press for sale’ and a local telephone number - in Melton Constable in fact. The man I bought it from had owned it for ten years but never used it, and before that it had been in a commercial printers in Aylsham. It weighs just over half a ton, and although it comes apart into four pieces it is enormously difficult to move. We have moved it twice - from Melton Constable to my studio in Aylmerton and from there to this house in Norwich - and I hope I never have to move it again. When we brought it here the removal people built a steel pathway through the door and through the house, and there it stands, dominating my printing room and enabling me to produce my prints.

Ivy Smith lives and works in Norwich as a painter and printmaker.

|