|

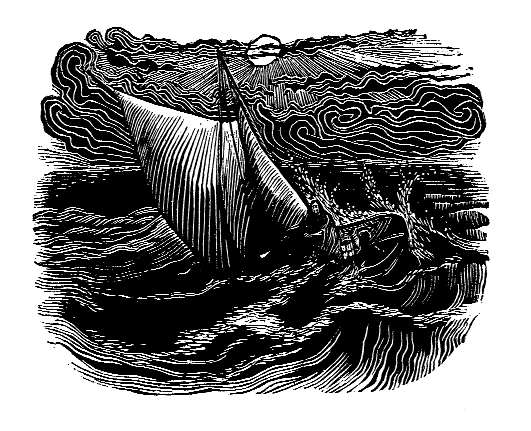

Why did you take up wood engraving?

I suppose I was about 27 when I came across wood engraving. I was at Cambridge, reading History of Art. I had originally studied art at the Slade, but I did no printmaking there. I had gone straight to the Slade from school, as did perhaps a third of the students; the others had been to art school already, which meant that they had been initiated into printmaking. It took a lot of courage – and I was not courageous – to enter the printmaking studios in complete ignorance and seek instruction. No introductory courses were organised. One had to ask some other student, busy with his own work, what to do next. In these circumstances I managed to do one single-colour lithograph on a real block of stone, and that was all. Etching was far too complicated to undertake. I don’t think anyone did wood engraving, nor do I remember any mention of screen-printing.

How did you come across wood engraving?

My supervisor at Cambridge, Patricia Jaffé, was a wood engraver. She had studied under Leonard Baskin and was keen that I should try the medium. She had a printing press in Newnham and we used to work there. It was she who introduced me to the work of Thomas Bewick. I had already published one novel for older children and was working on another, set in the Yorkshire Dales, where I had taught art at a girls grammar school. I saw that wood engraving was the perfect medium to illustrate the printed word. It could be printed in the same process as the text and used exactly the same elements – discrete, unblurred, black marks on white paper – to bring an imaginary world before the mind’s eye.

I know that reproductions of your work in books 1nd magazines have disappointed you. Why is that?

The problem is that the black and white prints in the pages of magazines tend to look pretty woolly; like felted-up knitting. They have nothing of the crispness, the transparency that even the crudest wood engraving cannot help but have.

I can’t see what you mean.

Have a look though this magnifying glass. Admittedly the pixels are very small, but they give a furry edge to every diagonal. A fine white line across an area of black is a string of separate dots. You probably think I am making a fuss about something that nobody else will notice. After all, there are black and white photographs of oil paintings and watercolours amongst the illustrations here, postcard sized reproductions of huge paintings. The thing is that readers looking at them make allowances. They know that the pictures are not in black and white, and that they are much larger. It is the fact that they won’t know allowances have to be made in the case of my wood engravings that I regret. |

|

But your book about Yorkshire, back in the 1960s, before computers were used in printing – did that come out right?

In fact I was disappointed with that. The engravings tended to be over-inked, so that fine lines were lost. You see, I am difficult to satisfy. I decided that I had to get a printing press, like the one Patricia Jaffé had. I had to print my own engravings. One of the things I admired about Bewick was that he was a tradesman, not a fine artist. He produced and sold books and printed ephemera. In those days there were artists who produced history paintings and exhibited at the Royal Academy, just as there are artists today who win the Turner Prize and whose work is intended primarily for museums. I do not aspire to such art. I would rather be a tradesman producing things that people can buy.

So you decided to print your own books?

Books were a bit beyond me. Composing type is a slow and tedious process. What I produced was greetings cards. From a wood block you can take an almost limitless number of prints; a metal block wears down quickly, but wood does not wear. It can crack, if exposed to sunlight or heating, it can be scratched, but it does not wear. Etchings are printed in limited editions because the plate gets worn out in the process of printing. There is no reason for printing wood engravings in limited editions, except the spurious reason that it gives the prints rarity value. So I produced thousands of cards and sold them cheap. It delighted me when the street sweeper who swept my street came knocking at my door and bought my cards. He had made my acquaintance when I was sketching in the gutter.

What sort of cards did he buy?

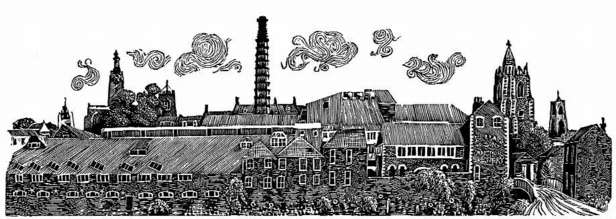

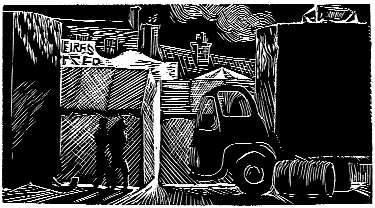

He liked the views of Norwich like this one of Bullard’s Brewery (see below) with its handsome chimney, long since demolished. Another line I did was cats. The Yorkshire book, A Cat Called Camouflage, had a cat in it; the blocks I had done for the book I used again to print cards. It taught me a useful lesson: you can always sell cats. So I made more cats. They sell well in Japan. I am still selling the same cat cards, after starting in 1977, the year I bought my press.

|

|

After I married I moved to Houghton St Giles, where the Slipper Chapel is, just outside Walsingham. The pilgrim shop at the Slipper Chapel commissioned several cards from me. When the Pope first visited England, there was hope that he would visit Walsingham. I hoped they would sell lots of copies of The Holy Mile which remains my favourite amongst all my engravings.

|

|

|

Tell me about your press. Where did you buy it?

I watched the pages of Exchange and Mart. I had to find one close to home because of the problems of transporting it. It came from West Walton. These presses were made over quite a long period, between about 1870 and 1920. This one has an open flywheel, which probably makes it quite early. Clothes or a hand could get caught in an open flywheel, so they became illegal. There were Health and Safety at Work regulations for craftsmen even then.

How did you get it transported from West Walton?

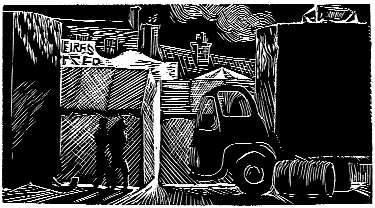

This was in March when the travelling showmen were at Wisbech Mart. Some of my fairground friends offered to help me collect it. So I hired a van and we drove out there. The lads shifted it up a garden so muddy that we couldn’t even put it on rollers to get it to the van! They had to lift it, but they were keen to show how strong they were compared to the ‘feeble joskins’ (their name for settled people)!

Fairground friends?

It’s corny, isn’t it? Local lady artist runs away with the raggle-taggle gypsies. The fairground was very beautiful in those days. Old fading canvas tilts at dusk received a bloom from the last light in the sky, while the lights underneath glowed through. Both putting up and pulling down had a magic. The pulling down, performed late at night and done as fast as possible, had the quality of a ballet, whilst the slower transformation of a familiar setting into the city of fun was always worth watching. I went to the fairground in the first instance to draw. But the travellers realised that the lady artist could be useful to them and help them with painting the shows. ‘Me Dad’s a great painter but he can’t do ladies,’ one of the boys said to me. The painted scenery was on hardboard using ordinary household paints. I became quite an expert at letters of blood and skeletons writhing in agony, though my lovely ladies were never quite saucy enough.

|

|

Do you still do work for them?

I still see the travellers when the fair comes to Norwich. The last job I did for them was to design a tombstone for ‘the old man.’

And do you still do engravings of the fairground?

I am planning some fairground engravings at the moment. There are still scenes which linger in my memory. Sometimes, years later you can see things more clearly in your mind’s eye than you could at the time. So I am hoping to recapture things I saw long ago.

Have you done any new cats lately?

I’m working on some right now. There is to be an exhibition of cat engravings next summer. But you should know that the Society of Wood Engravers doesn’t like cat prints in the Society exhibition. They think that cat prints give wood engraving a bad name; people will think all wood engravers are little old lady artists (like me) who stick to twee homesy subjects rather than tackling the realities and abstractions of contemporary art.

Do you work from drawings or photographs?

I work from drawings in the first instance although I do take photographs as well. Photographs are never as good as drawings. You can never capture that point of a movement which the eye recognises; you can seldom click the shutter at exactly the right moment, and ‘almost the right moment’ is never interesting or good enough. For example, when a cat stretches or yawns it is the final position which appeals and that may only be held for a fraction of a second. It is often useful to draw from a photograph and then go back to the live animal and draw. It helps you to understand what you are seeing.

From about 1967 to 1972 I took black and white photographs on the fairground with a Leica. I had two lenses, an Elmar for daylight and a Summitar for night-time scenes. There is something reassuring about having taken a photo. But then I could never wait until the film was finished, let alone developed, so I ended up working from drawings. I do the same thing today. Now I’ve got a cheap camera and I take colour photographs. There was a long period, 1972 to 1998, when I did not use a camera at all.

There seems to be a mythology around the special characteristics of wood blocks. Do you subscribe to that?

Most wood engravers used to buy their blocks from Lawrence’s in Bleeding Heart Yard. The address sounds as if they must have been trading there since the Middle Ages! In fact they didn’t move there until just after the war, though the firm goes back to 1859. And now, because London premises have become so expensive, they only trade over the Internet – times have changed. Boxwood makes the best blocks, though holly and some of the fruitwoods, lemon, apple and pear, are also acceptable. I’m planning to engrave a fairground scene on a large block which is made from a chopping board which came from IKEA. It’s a light coloured hardwood, very hard to tell what. I shall have to wait and see how well it works out.

Is there a tradition of working with old tools, or are modern ones just as good?

I’ve never heard of such a tradition. You need the tools to fit your hand. I have rather small hands and Mr Lawrence would cut the tools to fit me perfectly. Somebody gave me a second-hand set of tools with long shafts which have been useful in teaching pupils with bigger hands than mine. I have since lent them to another printmaker.

Isn’t it terrifying, cutting into a block and knowing that there is no going back? It’s not like painting. You can’t just over-paint or scrape away your mistakes.

I don’t ever feel comfortable starting a new block, making the first cut is terrifying. Although every cut could spoil the work, the first cut is the most worrying. Most creative work is done just below the level of consciousness – dictated by the muse, not driven by the maker’s own mind and will. Certainly I don’t work as if my intellect directed my hand. It’s different when I’m making drawings though; then a part of me is thinking about how I could render this or that in terms of cutting white out of black.

Are you ever tempted to produce work in colour?

I’ve never been able to think in the limited number of colours which printmakers use. There is one engraver, Edwina Ellis, who uses four blocks to produce full colour prints. She uses the four registration colours which all printers use – magenta, cyan, yellow and black – to produce full colour prints. But to me, it’s making decisions about how to cut the block, using the language of just black and white (a mark on the paper or no mark) as my only resource to create the effect and the picture I want. That seems to me the most challenging and satisfying thing.

Weren’t you living in Cromer when I first met you?

Yes, we had a lovely house in Cromer, looking down on the beach and the pier.

We moved there in 1986. Also in that year I had a commission to illustrate two books for a Japanese publisher. Later that publisher produced a Japanese edition of A Cat Called Camouflage. The translator became a friend started selling my prints and cards in Japan and she still sells them.

It must have been about the time we moved to Cromer that I abandoned my principles. I started to produce prints in numbered editions. I found it easier to sell prints through exhibitions. I still feel that wood engravings are unsuitable as pictures to hang on a wall. They should be held in the hand, on the page of a book, as a letterhead, or a greetings card. But people seem to want to buy them as pictures and I have given in. After we moved to Cromer I had some commissions from the National Trust, for cards, and also for their magazine. But much of my work each year was to produce one or two engravings for the Society of Wood Engravers exhibition from which I could expect to sell several prints.

I know one of those exhibition pieces: The Cromer Triptych. What made you do that print on three separate blocks?

Japanese woodcuts are often done as diptyches or triptychs. You will find that though they form one continuous picture, each section concentrates at a different focal distance: at the left will be a group on a terrace in the foreground, perhaps; the next draws our attention to the middle distance; and the third to the far distance. Each section is a picture in itself, and yet each plays its part in the picture as a whole. I have tried to do the same thing in this picture: the lighthouse at the left is close at hand, on the same level as the viewer; on the middle block the ground sweeps downhill and we look into the middle distance and beyond as far as Beeston Hump; while in the third block we look over the edge of the cliff and down to the beach below and the sea.

Is this the only time you have combined blocks in this way?

So far, yes. But I hope to do it again, perhaps showing a different time in each block, so that you get the continuous picture but each block gives you a different stage in the erection of a big ride on the fairground.

|

| |